Editor’s Note: The following guest blog post was written by published historian B. Travis Wright of Preserve Rollins Pass. Rocky Mountaineer’s team has relied on Travis for historical imagery, fact verification, and original maps to enrich Mile Post, our onboard publication for our Rockies to the Red Rocks route. His expertise ensures historical accuracy in our coverage of the Moffat Tunnel and Rollins Pass. We hope you find his insights as fascinating as we do.

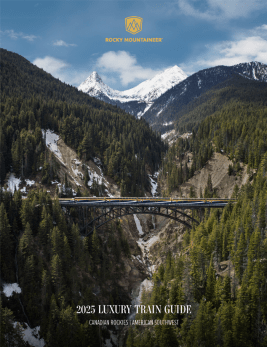

Picture this: it is the summer of ’25, and excited tourists arrive early at the train station, their anticipation crackling through the morning air. The first glimpses of the train send a shot of adrenaline through the crowd. The rising sun glistens off the coaches—perfect, immaculate, and polished to a mirror sheen, reflecting the golden morning light of Denver, Colorado.

Cameras at the ready, eager onlookers strain for a better view of the engine, its rigid metal skin encasing a powerhouse that sends deep vibrations through the ground—a resonating hum, power held in check. For those who step closer, the faint scent of heated oil and fuel carries the unmistakable promise of motion, of strength waiting to be unleashed.

Hisses, pops, and squeaks punctuate the air—not alarming but exhilarating, a mechanical fanfare, a symphony of steam and steel heralding the journey ahead. The excitement is tangible: on the platform, passengers bustle—some fanning themselves with newspapers, others ensuring their tickets are in hand. All eyes are on the friendly crew, the growing crowd silently wishing for those two magical words to be shouted:

“All aboard!”

A passenger train idles in Tolland, Colorado. To the right, Giant’s Ladder rises along the initial grades of the eastern approach to Rollins Pass. This section of the route, once a vital link for rail travel across the Continental Divide, challenged locomotives with its relentless incline and unforgiving conditions. More than 120 years later, Rocky Mountaineer rolls through this same historic corridor, tracing the path of pioneers and railroaders who once braved the high-altitude terrain. Collection: Preserve Rollins Pass.

As Denver’s skyline fades into the distance, the train steadily gains elevation, weaving through the foothills of the Rocky Mountains on twin ribbons of steel. It darts in and out of short tunnels, each exit revealing ever-expanding views—vast pine forests stretching to the horizon, elk and deer moving silently through the trees, and rivers swollen with freshly melted snow, tumbling over rocks as they race downhill. The rhythmic sway of the train, the panoramic windows framing a world in motion, and the quiet murmur of conversation blend seamlessly with the soft clink of glassware and the indulgence of decadent appetizers, making the journey as captivating as the landscape unfolding outside.

The train reaches the timeless Tolland Valley, where a lone one-room schoolhouse stands in the foreground, dwarfed by the towering presence of Giant’s Ladder—the dramatic, switchbacking ascent that will carry the train up the initial grades of Rollins Pass. We move as far west as we can, catching a fleeting glimpse of where the Moffat Tunnel is being carved into the shoulder of James Peak. But there is no tunnel—only a construction site, an ambitious vision still taking shape—after all, it is the summer of ‘25—1925. With no passage through the mountain, we U-turn to make our climb.

Tourists from around the world gathered for a commemorative photograph at Corona Station, the famed “Top of the World” on Rollins Pass, where they marveled at snowfields that refused to melt—even in the heat of summer. Along this breathtaking route, which operated from 1904 to 1928, passengers could clutch a snowball in any month of the year. Collection: Preserve Rollins Pass.

Almost immediately, the tracks steepen to a grueling 4% grade, forcing the engine to work at its limits. Chuffing, pounding, clanging, thundering—the resonance of the locomotive echoes through the valley, each rhythmic movement a testament to the raw power needed to climb higher. As the train ascends, the air outside grows thinner, cooler, and crisper, heightening the anticipation of those aboard. Click-clacking over wooden trestles, sweeping around alpine lakes encircled by rails, the journey becomes as mesmerizing as the landscape itself—each turn revealing views that command awe.

We seem to scrape the piercing blue sky, the train climbing ever higher until forests far below shrink to mere blades of grass. Through the windows, timeless snowfields stretch across the rugged terrain, remnants of winter refusing to yield to summer’s touch.

At over 11,676 feet (3,559 meters) above sea level, we pose beside the iconic sign, proof that we’ve reached the top of the world. Snowballs fly in July, cameras capture the moment, and we stand in awe of the sweeping landscapes that stretch endlessly in every direction—vast, wild, and untouched, a place where the past and present converge in the thin mountain air.

The Rocky Mountaineer train entering the Moffatt Tunnel in present day.

In the present day, trains have not reached this summit in nearly a century—abandoned after the completion and opening of the 6.2-mile-long (9.98 kilometre) Moffat Tunnel in 1928, which provided a faster, year-round route through the mountain that is impervious to winter snows or summer rains. The world has changed, but the pull of incredible scenery by rail remains. The need to climb higher, to see farther, to experience the landscape as those before us did—it never fades. We do this because our ancestors—and their ancestors before them—found immeasurable joy in rail journeys. No matter the era, we are drawn to the experience, compelled to gaze through windows at breathtaking landscapes and venture to places that feel both familiar and distant, close to home yet just far enough away to stir a sense of adventure.

Today, Rocky Mountaineer honours that spirit of discovery and traces much of the route of the legendary Moffat Road amid the Colorado Rockies, where rails still wind through towering canyons and past rushing rivers, climbing toward—and into the heart of the Continental Divide by way of the historic Moffat Tunnel. Though the train no longer scales the heights of Rollins Pass, Rocky Mountaineer passengers can still glimpse Giant’s Ladder—a silent, historic remnant of the switchbacking climbs that once carried trains toward the summit of Rollins Pass, where the echoes of that pioneering ascent remain etched into the landscape—a landscape shaped by time, perseverance, and a relentless push westward.

The Moffat Road to Rollins Pass was advertised as a one-day excursion (8:15 a.m. to 6:30 p.m.), promising travelers the “scenic wonders of a lifetime.” One such wonder was summer’s glow—seen here as alpenglow illuminates the summit of the pass, Corona Lake, and the Indian Peaks Wilderness, as viewed from Mount Epworth. This ephemeral radiance, lasting mere moments, adds a touch of brilliance to an already awe-inspiring landscape. Collection: Preserve Rollins Pass.

A century ago, the journey over Rollins Pass was billed as the “greatest one-day scenic trip in the world”—a dramatic climb that peaked at the Continental Divide. One day, one summit, one breathtaking moment at the top. Today, the experience stretches beyond a single ascent, unfolding over two days and carrying travelers far past Colorado’s high country into the vast, otherworldly red rock landscapes of Utah and onward to Moab. Rocky Mountaineer’s “Rockies to the Red Rocks” isn’t defined by a single endpoint—it’s about a journey twice as long, twice as varied, and every bit as breathtaking as the landscapes of the West and the American Southwest.

Rocky Mountaineer promises you’ll discover the unseen West—a journey that begins in the towering Rockies, where history lingers in alpine valleys and the echoes of locomotives still drift through the crisp mountain air, before descending into the red rock canyons of the American Southwest, where the backdrop tells its own ancient story. The spirit of adventure endures, drawing travelers to landscapes unchanged by time—to valleys and ridgelines, to rivers that remain as wild and untamed as they were a century ago.

We go not just to see, but to connect—to trace the routes carved by those who came before, to stand where history unfolded, and to leave knowing that time moves forward, but some places will always call us back. Beneath boundless skies, the journey isn’t just about reaching a destination—it’s about rediscovering the wonder of the West and the American Southwest—from soaring peaks to sculpted red rock landscapes, one breathtaking mile at a time.

B. Travis Wright, MPS | Preserve Rollins Pass